We know a lot about the ancient Minoans: their religion, their daily lives, their trades, even their cooking. But one subject remains a source of controversy in spite of it all: whether or not the Minoans were a militarized culture.

My purpose today is not to argue one way or another (though I do have an opinion). My purpose is to examine why so many people feel compelled to try to prove that the Minoans were a militaristic society. I think this issue says at least as much about us as it does about the people of ancient Crete.

This issue is related to the need many people have to prove that the Minoans had a monarchy instead of being ruled by councils or collectives of leaders. Sir Arthur Evans, the Victorian-era archaeologist who first unearthed the Minoan city of Knossos and revealed it to the modern world, was just sure that the Minoans had a king who ruled over them, just as his beloved British Empire had a monarch. Otherwise, he reasoned, how could they possibly have become such an advanced civilization? So he named the parts of the Knossos temple complex with terms like Throne Room and Queen’s Megaron. Those names have stuck even though we’ve figured out since Evans’ time that the huge building was an administrative and religious temple complex and not some monarch’s palace. But Evans couldn’t envision a world in which successful cultures arose with cooperative or even oligarchic structures instead of monarchies. And many modern people can’t envision a thriving civilization that doesn’t have a military and a desire for conquest.

When modern people look at ancient Crete, they see a successful society: wealthy, vibrant, worldly. And it makes many people profoundly uncomfortable to think that a culture like that could flourish without a military, without the thirst for blood and conquest. After all, in the millennia since the Minoan cities fell, human culture has been all about armies and conquest, generals and battles and taking what you want. Why should the Minoans be any different?

The thing is, if ancient Crete was different, if the Minoans managed to create their incredible civilization without a military, or with nothing more than a simple merchant marine to protect their trading ships, that means it’s possible to be successful without being a militarized dominator society. That means that militarization, institutionalized violence, and domination are choices, not inevitabilities. And that makes us accountable for the misery, hardship, and atrocities we’ve perpetrated in our own militarized societies.

This is why, every few years, someone comes out with a paper purporting to show that the Minoans had a military and were a warrior culture: We need to justify our own horrors. We need to show that we can’t help it, that wanting to dominate and take and kill is an ingrained part of the human condition and not a choice. We’re mirroring our own shadows in the history we’re trying to write.

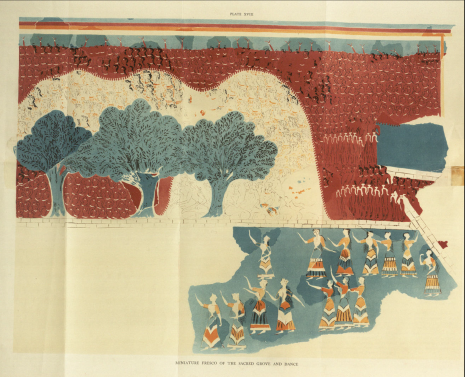

Ancient Crete was no utopia, but it was an egalitarian society with a deep sense of the sacred. Instead of trying to make excuses for our own horrible behavior, how about we look to ancient Crete for ways we can do better instead?