One of the great things about Ariadne’s Tribe is that it isn’t a rigid path, but a growing tradition with a broad scope that allows each person to find their own right relationship with the Minoan deities. We do share the pantheon (we call them the family of deities) and a good handful of practices, but there’s a lot of leeway within those boundaries.

But that can be a problem, too, because there aren’t pre-set rules for things like how to set up your altar.

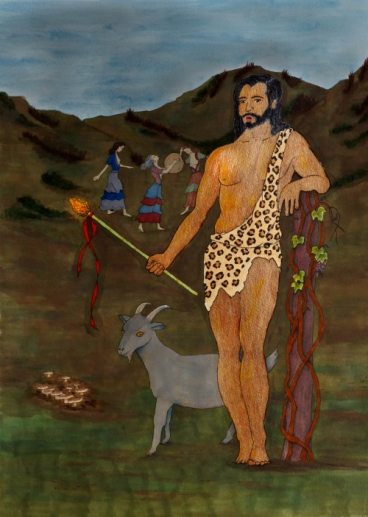

My Pagan training began with Wicca, which has clear rules for choosing and organizing the items that go on an altar, even down to what you do at different points on the Wheel of the Year. So how do you set up a Minoan altar if there aren’t any rules? There may not be rigid rules, but there are guidelines that can help you create an altar that’s just right for you to connect with the deities. (That’s my Minoan altar up top.)

I’ll guide you through some concepts below. But remember, the most important thing is always to listen to the deities. Being in relationship with them is the whole point of setting up an altar in the first place.

My book Labrys and Horns has details about setting up your sacred space, consecrating your altar, and calling the deities. But there are some basics that will get you started, and some things you ought to know that are different from other types of modern Paganism.

First of all, we have no evidence that the Minoans used the classical (Hellenic) four-element system of fire, air, water, and earth. That appears to have been created much later than Minoan times (the Hellenic Greeks flourished centuries after the fall of the Minoan cities). But the Minoans did pay special attention to the cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) as well as the places along the horizon where the Sun, Moon, and certain stars rose at different times of the year. These directions were important enough to the Minoans that they oriented their temples, peak sanctuaries, and tombs toward them. So you could “frame” your altar with small objects that are located toward the cardinal directions, if that appeals to you.

Then there are the deities. Which one or ones does your altar honor? Will that change over the course of the year? Where will you start? What objects will you use to represent or honor them?

My altar, pictured above, currently includes the Melissae, Amalthea, and Ariadne. These three “play well together” so I can put them together on the same altar without a problem. I’ve found that’s not the case for Dionysus; he tends to want a dedicated altar space all his own (which he has elsewhere in my house). So first you need to decide who the focal point will be. Then, if you want to include more than one deity, check (via meditation or your other preferred method) to make sure that will work. The only surefire “multi-altar” I know of is one that honors the Minoan pantheon as a whole, without focusing on any specific deity. If you want to honor particular gods and/or goddesses, please be sure to ask them how they would like to be represented and whether they’re OK with being included alongside others on your altar.

Once you have all the items arranged, you’ll want to consecrate your altar and begin using it: making offerings, meditating and praying in front of it, maybe even performing rituals if that’s your thing.

An altar is a wonderful thing. It’s a physical anchor for spiritual practice, a focal point that reminds us of our priorities every time we pass by it. It can be as simple as a few items on a bookshelf (I have several of those – my non-Pagan friends think I have interesting knick-knacks!) or as fancy as a whole room dedicated to your path.

Whatever your altar looks like, however it’s arranged, make sure it works for you and the gods with whom you’re building a relationship. Because more than anything, an altar is the meeting place between you and the divine.